The Realities of Easter

Introduction

Only eternity will reveal how many people have turned away from the truth because of the influence of pagan traditions. The warning that the Lord gave to Israel is very clear: “After the doings of the land of Egypt, wherein ye dwelt, shall ye not do: and after the doings of the land of Canaan, whither I bring you, shall ye not do: neither shall ye walk in their ordinances. Ye shall do my judgments, and keep mine ordinances, to walk therein: I am the LORD your God” (Leviticus 18:3-4). Israel was to walk in the ways of the Lord, not after the traditions of the Egyptians, nor after the manner of the people whom they would supplant in the land of Canaan. Through Jeremiah, the Lord declared: “Learn not the way of the heathen …” (Jeremiah 10:2); yet what is largely accepted as commonplace among Evangelicals today, often finds its roots within the pagan traditions of fallen cultures. Although we might rightly ascribe the responsibility to the Roman Catholic Church for making many of these customs part of our culture, we cannot blame them for our decision to accept them as appropriate for the child of God. Growing up with error only serves to make it more difficult to identify, but it does not make it right. We might feel that the customs of our youth are acceptable without so much as a second thought – but will they stand the test of Scripture?

When my wife and I stepped away from Evangelicalism, it soon became evident that there were many things that we had accepted as being right that needed to be re-evaluated in light of our new commitment to the truth of Scripture. This study is another that I undertook to ensure that our practice was in keeping with the teachings of God’s Word; since that was now our greatest concern, our accepted traditions were brought under the revealing light of the holy, unchangeable Scriptures. Perhaps one of the greatest failures of Evangelical teaching is that there is no encouragement to personally study the Scriptures even though that is what God requires of us; in fact, even the preachers and teachers seem content to accept the traditions that they have been taught as having God’s stamp of approval, without ever checking to ensure that they do. I will never forget the response that I received from an elderly, fundamental-Baptist preacher when I asked him to review the exaggerated case that one of his missionaries had made for a Biblical basis for church membership; his response was simply: “I am a Baptist by conviction. I believe our faith and practice is absolutely inline with what the Word of God teaches.”1 In other words, he believed that his Baptist traditions had God’s approval, yet he was unwilling to test those beliefs to ensure that they were, in fact, in keeping with God’s Word (contrary to 2 Corinthians 13:5); his thought was that if you have a problem with his Baptist traditions, then clearly you’re not a Baptist, and that’s okay (although clearly not the best). His attitude provided me with encouragement to continue to measure all things against the Word of God, to teach what I found to my wife, so that we could change how we lived in order to remain obedient to the commands of Scripture. We have changed many things since leaving the Evangelical community, and it has cost us family and friends, but we are committed to continually seek to know the Truth of God more fully – indeed, His promise is that the one who is diligently seeking is also finding (Matthew 7:8).

As we consider the subject of Easter together, may it be with a desire to know what God has to say on the matter. Within most churches, there are deeply entrenched traditions when it comes to how this time is celebrated, but, if you’re like I was, you may have never taken the time to ask any questions as to why these things are done – perhaps this will be your maiden voyage into discovering the truths of Scripture as never before. It was for my wife and me; God bless you as you read on.

Easter - What’s in a Name?

There is perhaps no greater example of how we have submitted to tradition and failed to exercise our minds in spiritual matters than in the consideration of Jesus’ death and resurrection, and the annual event that is commonly known as Easter. Although the word Easter does appear in Acts 12:4 in the King James Version (KJV), it is an incorrect translation of the Greek word pascha, or Passover; interestingly, the other 28 times that pascha appears in the Greek text, it has always been correctly translated as Passover, nor has it been translated as Easter in most modern translations.2 The translators of the KJV were instructed by King James to follow the pattern of the Bishop’s Bible in carrying out their work, and for some reason, they felt justified to follow that Bible rather than the Greek text;3 the Bishop’s Bible was hastily produced by a number of Anglican bishops in an effort to provide an acceptable alternative to the Geneva Bible, which had become very popular in England and was perceived to be largely Calvinistic because of its many notes.4 Even though the translators of the Bishop’s Bible (1568, and significantly revised in 1572) translated the Greek word pascha elsewhere as Passover, in Acts 12:4 and John 11:55, they chose to use the word Easter, and the KJV translators perpetuated the former error.5 Wycliffe’s translation of 1395 correctly translates the Greek as Passover, however, the subsequent translations done by William Tyndale (1525) and Miles Coverdale (1535) both used the term Easter. Why Tyndale would have done so is somewhat mystifying, as it is said that he translated directly from the original languages.6 Coverdale, on the other hand, depended largely on Tyndale’s work, as he did not have the same grasp of the languages.

The etymology of the word Easter shows its origin in the “O.E. [Old English] Eastre (Northumbrian Eostre), from P.Gmc. [Proto Germanic] Austron, a goddess of fertility and sunrise whose feast was celebrated at the spring equinox.”7 The Roman Catholics, however, do not accept this history for the word, and declare: “The English term [Easter], according to the Ven. Bede [the Venerable Bede, one of their Doctors of the Church, c. AD 672-7358] … relates to Estre, a Teutonic [northern European] goddess of the rising light of day and spring, which deity … is otherwise unknown … The Greek term for Easter, pascha … is the Aramaic form of the Hebrew pesach (transitus, passover)” (bold emphasis added).9 Despite the fact that one of their own (Bede), whom they consider to be a significant contributor to the formulating of their doctrine, exposes the pagan connection, Roman Catholic theologians have chosen to dismiss this association and prescribe Easter as being a correct translation for the Greek word, pascha. However, even though they distance themselves from the pagan relationship and seek to uphold a false translation of the Greek word pascha, their own English Bible translations do not use the term Easter for pascha in either John 11:55 or Acts 12:4.10 Even the oldest Catholic translation of the Bible into English (the Douay-Rheims translation; NT published in 1582) translates the word as pasch, not Easter.11 There appears to be some inconsistency among Catholic scholars as to the correct translation of the Greek pascha, or perhaps they are seeking to justify their general use of Easter.

However, the Roman Catholics are not the only ones who choose to turn a blind eye to the relationship between the word Easter and the pagan goddess of fertility. The late Gretchen Passantino, co-founder of Answers in Action and a contributor to the Christian Research Journal, stated: “Easter is an English corruption from the proto-Germanic root word meaning ‘to rise’.”12 She went on to explain: “It refers not only to Christ rising from the dead, but also to his ascension to heaven and to our future rising with him at his Second Coming for final judgment. It is not true that it derives from the pagan Germanic goddess Oestar or from the Babylonian goddess Ishtar ….”13 This is an attempt by a fairly well-known Evangelical apologist to rationalize the “English corruption” Easter sufficiently so as to make it completely acceptable by denying the pagan connection. Regardless of the spiritual significance that she attempted to assign to the word Easter, the position that she put forward, supposedly debunking the pagan association, was based entirely upon her own authority. She flatly denied that Easter derives from the names given to pagan goddesses going back to Babylon, yet she did not provide any support for her assured declaration. On the other hand, the evidence against her in this matter seems to be quite significant. We have already seen the analysis made by one etymology dictionary that is in opposition to her position. Shipley, in his Dictionary of Word Origins, says that the word is “from the AS [Ango-Saxon] Eostre, a pagan goddess,” and then goes on to state: “The Christian festival of the resurrection of Christ has in most European languages taken the name of the Jewish Passover … in Eng. [English] the pagan word has remained ….”14 He not only identifies Easter as being of pagan origin, but goes on to expose the English language as being quite unique in retaining the pagan term. Another states: “It is significant that in England and Germany the Church accepted the name of the pagan goddess ‘Easter’ (Anglo-Saxon Eostra – her name has several spellings) for this new Christian holiday.”15 Passantino’s opinion on the matter stands alone against some very significant authorities; as nice as it might have been for her to think that the word Easter sprang directly from reference to the resurrection of the Lord, it was clearly only a delusion on her part.

It is commonly held among professing pagans that Eastre is the Anglo-Saxon goddess of fertility, and Ostara is the Germanic goddess and the name of the spring festival that celebrates a time of renewal and rebirth.”16 It seems that all of the ancient civilizations had their version of this goddess of fertility: the Ango-Saxons had their Eastre, Egypt had Isis, Phoenicia - Astarte, Greece - Aphrodite, Rome - Venus, Babylon - Ishtar, and the inhabitants of Canaan had Ashtoreth (1 Kings 11:33). Like many other traditions that are a part of our culture today, the roots of Easter can be traced way back to the Babylonian civilization that was formed out of rebellion against the Lord.

From the descendants of Noah, we find a great-grandson, Nimrod, whose name means “we will revolt.”17 He became “a mighty one in the earth” (Genesis 10:8), which speaks of his greatness as a leader among the people, and a “mighty hunter before [against] the Lord” (Genesis 10:9) that exposes his rebellion against the God of creation.18 If we understand that it is not possible to be in rebellion without first knowing something about what or whom you are rebelling against, then the truth of Romans 1:21 becomes much more striking – “…when they knew God, they glorified him not as God, neither were thankful; but became vain in their imaginations, and their foolish heart was darkened.” Nimrod led a rebellion against God, which simply means that he knew enough about what God required to be fully aware that his actions were in opposition to Him. That rebellion found its ultimate expression in the city and tower that he set out to build in defiance of Jehovah (Genesis 11:4), a city called Babel (Genesis 10:10, 11:9).

Almost all pagan cultures celebrate the vernal equinox in honor of a goddess of fertility: Asase Ya (Ashanti people of west Africa), Isis (Egypt), Bhavani (India), Asherah (Mesopotamia), Éostre (or Ostara, German), Aphrodite (Greek), and Venus (Roman), to name just a few.19 As we have seen, the Catholics, and even some Evangelicals, will attempt to refute the pagan history of Easter (while most will simply ignore it). It cannot be denied that modern-day pagans readily accept this connection: “Easter has deep roots in the mythic past. Long before it was imported into the Christian tradition, the Spring festival honored the goddess Eostre or Eastre.”20

As we consider the use of the term Easter within the context of our cultural celebrations, if we’re honest, we will acknowledge that not everyone has Jesus’ death, burial and resurrection in mind. Nevertheless, it is also evident that, as it is applied to the events surrounding the culmination of Jesus’ earthly ministry, the term is used by virtually everyone today – Christian and pagan alike; however, that does not make it right. We would do well to take to heart the words of Jehovah through Jeremiah that we have already noted: “Learn not the way of the heathen, and be not dismayed at the signs of heaven; for the heathen are dismayed at them” (Jeremiah 10:2). This was a warning to Israel that they were to be a separate people, and, likewise, it is a warning to us to guard against being taken in by the ways of the world.

We have already noted the warning that the Lord gave to Israel before they ever entered the Promised Land (Leviticus 18:3-4) – a warning to be separated from the traditions of the pagan cultures of Egypt and Canaan. The Lord’s specific instructions to Israel was that they were not to adopt the pagan customs of the people where they were going (Canaan), nor were they to take with them the practices of the people whom they had left behind (Egypt). God desired a holy people: “… if ye will obey my voice indeed, and keep my covenant, then ye shall be a peculiar treasure unto me above all people: for all the earth is mine: and ye shall be unto me a kingdom of priests, and an holy nation” (Exodus 19:5-6); yet as we consider Israel’s history, we realize that God’s desire for them never happened. Interestingly, we find that Peter made a similar comment regarding those who are in Christ: “…ye are a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, an holy nation [people], a peculiar people [an acquired people]; that ye should shew forth the praises of him who hath called you out of darkness into his marvellous light” (1 Peter 2:9).21 Yet, what do we find today among those who claim to be God’s people? When they speak of Jesus’ death, burial and resurrection, they refer to it by the name of a pagan goddess of fertility whom pagans celebrated at the time of the spring equinox. Surely Satan must laugh at the gullibility of today’s professing Christians; he has managed, while working through a corrupt branch of church history, to get Christians everywhere to refer to the greatest demonstration of God’s love for mankind by the name of a pagan goddess. How could we? How dare we so profane God’s righteous act of sacrifice to secure our redemption! Although we may be gratified that we are not following “after the doings of the land of Canaan” (we are not following the pagan rituals of our society), yet we may well be guilty of perpetuating “the doings of the land of Egypt” (continuing the error from past days).

Constantine I

How did we fall into this trap of perversion? Once again, we need look no further than the budding Roman Catholic Church of the fourth century. In an effort to settle what had become a rather lively dispute as to when the death, burial and resurrection of the Lord should be remembered, the determination of when Easter was to be celebrated was made by the Council of Nicea in the year AD 325. “These Paschal controversies … ended with the victory of the Roman and Alexandrian practice of keeping Easter … on a Sunday, as the day of the resurrection of our Lord.”22 Although the specifics of this did not come out in any of the canons of the Council, their determination was this: “The feast of the resurrection was thenceforth required to be celebrated everywhere on a Sunday, and never on the day of the Jewish passover, but always after the fourteenth of Nisan, on the Sunday after the first vernal full moon.”23 The circular from the Council of Nicaea that was sent out by Emperor Constantine declared: “we would have nothing in common with that most hostile people, the Jews”; in other words, “the leading motive for this … [calculation of when to celebrate Easter] was opposition to Judaism.”24 Although the consensus was that it was to never fall on the day of the Jewish Passover, they had no problem aligning it with the common godless (and goddess) celebrations. At the time of Constantine, there was a growing undercurrent of anti-Semitism that was often reflected in the decisions that were made – they could practice anything except that which gave the appearance of being remotely Jewish. What is beyond comprehension, is that they shunned anything Jewish (even though Jesus was a Jew) yet had no difficulty embracing what was totally pagan – one more time, Satan could laugh at the spiritual efforts of self-righteous men. This became the pattern that the leaders of the emerging Roman Catholic Church followed in a twisted effort to make “Christian” celebrations the practice of the majority of the common people – something that would garner the favor of the emperor, which they sought with a growing frenzy. By using the pagan festivities that already existed, the bishops simply changed some of the names involved; the pagans didn’t care as they were used to the names being changed, and the “Christians” could then celebrate at the same time – everyone in the empire would be together during the days of the festival. A thin veneer of “Christian” whitewash was all that was needed to unite the empire, gain the favor of the emperor, and everyone was happy, but no one considered that God would not be impressed. Today, sincere Evangelicals and Fundamentalists speak the name of the ancient goddess of fertility without a second thought, and they faithfully train the next generation to perpetuate the error – something that must be particularly loathsome to our holy God.

When Joshua reached the end of his life, he spoke words of encouragement and challenge to the leaders of Israel: “Be ye therefore very courageous to keep and to do all that is written in the book of the law of Moses … that ye come not among these nations, these that remain among you; neither make mention of [or, invoke] the name of their gods … But cleave unto the LORD your God …” (Joshua 23:6-8).25 In this, he echoed Jehovah’s words through Moses: “…in all things that I have said unto you be circumspect [take heed, guard]: and make no mention of [do not invoke] the name of other gods, neither let it be heard out of thy mouth” (Exodus 23:13).26 The Psalmist, likewise, understood the Lord’s requirement in this regard: “Their sorrows shall be multiplied that hasten after another god: their drink offerings of blood will I not offer, nor take up their names into my lips” (Psalm 16:4). Is it a small thing that the name of the goddess of fertility slips unnoticed from the tongues of Christians today as they refer to the sacrifice of the Lord Jesus Christ for the sins of the world? Paul asked this question: “What fellowship hath righteousness with unrighteousness?” (2 Corinthians 6:14) – the required answer is still, “None!”

The text of Scripture declares: “For I have received of the Lord that which also I delivered unto you, That the Lord Jesus the same night in which he was betrayed took bread: And when he had given thanks, he brake it, and said, Take, eat: this is my body, which is broken for you: this do in remembrance of me. After the same manner also he took the cup, when he had supped, saying, This cup is the new testament in my blood: this do ye, as oft as ye drink it, in remembrance of me. For as often as ye eat this bread, and drink this cup, ye do shew the Lord’s death till he come” (1 Corinthians 11:23-26). This is the Biblically-prescribed method for remembering the Lord.

Today there are elaborate dramatic presentations of the “passion play” all around the world (depicting the events surrounding Christ’s crucifixion), and many churches are sure to include a dramatic production of some aspect of the Lord’s suffering during the spring season. Perhaps the most well-known, large-scale production is Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, which not only went to great lengths to dramatize the gore of the crucifixion, but also very carefully followed the Roman Catholic tradition of the Stations of the Cross. The dramatic plays have become a tool used by Satan to draw everyone together in Ecumenical unity and cooperation; our local ministerial association has not been exempt from such doings – but why would they be? This is the whole point of coming together. The passion play concept became a part of the early church rituals during their “Good Friday” celebrations (again, this is something with a long-standing history). Then, in the 19th century, there began a rejuvenation of the historic plays, and they have continued to grow in popularity.27 However, this is not how the Lord arranged for us to commemorate His death; He has laid out very clearly how we are to remember Him, and it includes no dramatic recreations of what we think might have taken place at Calvary, or anywhere else; beyond that, one thing is absolutely certain – there is undeniably no call to commemorate Christ’s suffering under the name of a heathen goddess.

Good Friday & Easter Sunday vs. Truth

As we consider Good Friday (commonly thought, by Evangelicals, Fundamentalists and Liberals alike, to be the day of Christ’s crucifixion), it is important that we base our understanding of the timing of the events surrounding Jesus’ death, burial and resurrection on reality, and not on what has been passed down to us. Today’s calendar shows a day called Good Friday followed by a regular Saturday, and then Easter Sunday. Typically, the understanding is that Jesus died on Friday, and was raised to life on Sunday; this fits nicely with our inherited calendar and the way that Easter is celebrated today (using the term with the full understanding of its pagan origins). To quote from Hank Hanegraaff, director of the Christian Research Institute and host of the Bible Answer Man radio program, “In Matthew 12:40 Jesus prophesies that He would be dead ‘three days and three nights.’ The fact of the matter is he was dead for only two nights and one full day.”28 He justifies this blatant contradiction of Jesus’ own words by saying that the Jews counted any portion of a day as a whole day. However, Jesus’ words to the Pharisees that Hanegraaff so casually dismisses, seem very clear: “For as Jonas was three days and three nights in the whale’s belly; so shall the Son of man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth” (Matthew 12:40). Why would Jesus, the eternal Word Who framed the first evening and morning (Genesis 1:5), say “three days and three nights” if He meant only one day and two nights? Specifically stating “three days and three nights” would rule out Jesus counting a portion of a day as the whole day; He is very specific about the number of days and nights that would be involved. Counting from Friday to Sunday will never permit the fulfillment of these words of Jesus, yet this is rationalized away, and the average Evangelical today, including the so-called “Bible Answer Man,” carries on without giving the matter another thought. Even more surprising, it seems that even the very vocal Fundamentalists, who are often critical of Evangelicals, have joined the mindless by “going along” with the crowd rather than seeking the truth, and then doing their part to make that truth known. It is way too late to stem the slide, but it’s never too late to stand for the truth.

In light of the terrible desecration of calling our Lord’s death, burial and resurrection by the name of a pagan goddess, it is incumbent on us to give careful consideration to the timing of the events of Jesus’ sacrifice and resurrection so that we do not add thoughtless error to blasphemy. We have already seen Hanegraaff’s careless acceptance of the Catholic tradition (for that’s exactly what the “Good Friday-Easter Sunday” combination is), and we must be cautious that we do not fall into the same simplistic, non-thinking pattern. To begin our consideration, it is important that we hold in our minds that the Jewish method of keeping time is not the same as what we practice in our culture today. The Jewish day begins at about six o’clock in the evening, and is in keeping with the Genesis account of creation where God declared the “evening and the morning” to be the day (Genesis 1:5, 8, 13, 19, 23, 31). We need to keep this firmly in mind when viewing the events surrounding Jesus’ death and resurrection, lest we arrive at conclusions that are based on an incorrect premise.

Leviticus 23:5 tells us that “in the fourteenth day of the first month at even is the Lord’s passover.” The first month in the Jewish calendar is called Abib or Nisan (the latter was primarily used after the Babylonian captivity, and seems to be rooted in the Assyrian word nisannu, meaning “beginning”29). This is in the spring of the year, and is the month in which the Lord brought Israel out of Egypt. For ease of looking at the details of the days surrounding the Passover as they unfolded at the time of Jesus’ death and resurrection, it is of value to plot them into a chart format so that they can be observed clearly and chronologically.30 See Chart.

Incredibly, by taking the time to read the Scriptures carefully, it is not difficult to determine that Jesus fulfilled His statement to the Scribes and Pharisees that He would be in the earth three days and three nights (Matthew 12:40). It is not necessary to rationalize Jesus’ words away, or to manipulate the text in order to see that His words were fulfilled with great precision. For the purposes of our study, it is important to recognize two truths that have failed to hit the radar of Evangelicals and Fundamentalists alike: 1) the Lord Jesus Christ did not die on “Good Friday,” but rather on Wednesday, the 14th of Nisan, as our Passover Sacrifice (1 Corinthians 5:7), and 2) He did not rise on “Easter Sunday,” but rather at the end of the Sabbath, our Saturday evening. What we have seen in the Scriptures is a clear discrediting of the modern concept of “Good Friday” and “Easter Sunday” – products of the zealous Roman Catholic leadership to “Christianize” the pagan celebrations already in common practice. Once again, we must remind ourselves: “Learn not the way of the heathen …” (Jeremiah 10:2), and “… what communion hath light with darkness?” (2 Corinthians 6:14); the former being a “thus saith the Lord” to which we would do well to give heed, and the latter being a rhetorical question to which the answer is: “None!!”

Carnival or Mardi Gras

We might not typically relate what has become a time of wild partying as having any relationship at all with Jesus’ death and resurrection, and we would be Biblically correct. As I grew up, a carnival was always considered to be a travelling amusement show that would include rides, clowns, and cotton candy. However, historically, Carnival has referred to the general time before Lent, which is a season of fasting and self-denial leading up to Easter; today it is primarily the three days prior to Ash Wednesday (which signals the beginning of Lent), although there are still some regions that begin the celebrations as early as November. However, indications are that the celebration of life (Carnival) originally began December 26, and built to a climax just before Lent;41 the common element to all forms of this celebration is that it ends on the day before Ash Wednesday. The term Carnival comes from an old Italian word that literally means “raising flesh,” but folk etymology has it coming from Latin meaning “flesh, farewell.”42 Mardi Gras, as it has come to be known in many regions, is from the French for “fat Tuesday,”43 and gives some indication of the excesses that take place prior to the fasting period of Lent that begins the next day on Ash Wednesday.

The Carnival celebrations date back to the ancient Greek spring festivities in honor of Dionysius, the god of wine.44 The Romans adopted the celebration and merged it with their Bacchanalia (a spring festival in honor of Bacchus, their god of wine and revelry) and Saturnalia (their celebrations around the winter solstice). The Roman Catholic leaders then adapted the pagan festival to lead up to their season of Lent, with the primary celebrations taking place just before Lent. In essence, it became a time of excess before a time of restraint. “Carnival … was a giant celebration in which rich food and drink were consumed, as well a time to indulge sexual desires all of which were supposed to be suppressed during the following period of fasting” (bold in original).45 Mardi Gras is not something that we typically associate with the Roman Catholic Church, perhaps a reflection of the Church’s desire to distance itself from the debauchery of this celebration. Nevertheless, the association with paganism is very evident, and the culmination of this festival lands on the doorstep of Lent, which we all relate to the Roman Catholic Church.

Ash Wednesday and Lent

Ash Wednesday is the first day of the season of Lent, a forty-day period of abstinence and reflection leading up to Easter (I freely use the term inasmuch as these all bear pagan roots). Ash Wednesday derives from the ancient practice of applying ashes to the head, or forehead, of an individual as a sign of humility before God. “Ash Wednesday is a somber day of reflection on what needs to change in our lives – if we are to be fully Christian.”46 Within the Catholic tradition, it is a time to ponder those things that we need to do differently in order to be “fully Christian”; it is another aspect of the works-oriented salvation that characterizes Roman Catholicism.

What is interesting to notice is that this practice, which has traditionally been connected with the Roman Catholic Church, has been quickly moving into Evangelicalism. Belmont University in Nashville, Tennessee, an Evangelical university with Baptist roots, in 2009 held an Ash Wednesday service led by a local Catholic bishop.47 In 2010, the service was co-officiated by Belmont’s own Vice-President of Spiritual Development; the Catholic Bishop of Nashville gave the message “followed by the marking of the ashes.”48 There is a movement among Evangelicals toward the liturgical – we see this very specifically evident within the Emergent church, where there is a very pronounced shift back to ancient practices (where they originate is not a matter of concern to them), and the Catholic Church is a primary source for most of these traditions.

The history of Lent seems to be cloaked in a shroud of mystery; claims are made that it was kept from the days of the Apostles but that is speculative – it is mentioned in the canons of the Council of Nicaea (AD 325).49 Canon V suggests a meeting of the bishops twice each year: “the one before Lent … and let the second be held about autumn”; lent is from the Latin Quadragesimae, which simply means the fortieth.50 Evidence for Lent being a fast of 40 days does not seem to appear until after the Council of Nicaea.51 Within the culture of ancient Egypt, Osiris (god of the dead and living [resurrected])52 was “supposed to be dead or absent forty days in each year” and during this time the people would mourn his loss;53 such rites were common among the ancient nations during the times when the land was unproductive, and this period of mourning was followed by a joyous celebration at the vernal equinox – the beginning of springtime.54 Although such pagan connections are generally not acknowledged by those who keep Lent (which now includes some Evangelicals), the reality is that there is no Biblical record establishing this tradition, but we find many warnings against adopting pagan practices. The Roman Catholic Church will, from time-to-time, admit that there is a pagan connection to many of its special days: “The reasons for celebrating our major feasts when we do are many and varied. In general, however, it is true that many of them have at least an indirect connection with the pre-Christian [pagan] feasts celebrated about the same time of year — feasts centering around the harvest, the rebirth of the sun at the winter solstice (now Dec. 21, but Dec. 25 in the old Julian calendar), the renewal of nature in spring, and so on.”55 The calendar of the Catholic Church is filled with festivities and commemorations that have grown out of their practice of “sanitizing” pagan celebrations. “They [the Egyptians] claimed the merit of being the first who had consecrated each month and day to a particular deity; —a method of forming the calendar which has been imitated, and preserved to the present day; the Egyptian gods having yielded their places to those of another Pantheon [Roman paganism], which have in turn been supplanted by the saints of a Christian [Catholic] era ….”56 Very little has changed; paganism willingly changes its appearance to find acceptance in every era – Satan loves religion and so changing names for different pagan deities is not a problem.

Within the Catholic tradition, the forty days of Lent are seen as a time of prayer, fasting and almsgiving in preparation for the celebration of the Easter season. This would be a time for the nominal Catholics to renew their fervency by going to confession and doing the prescribed penance – sacramental acts that bear soul-saving properties (according to their tradition).

However, as already noted, Lent is no longer just for pagans and Roman Catholics; Evangelicals are not about to be left behind in anything that will promote Ecumenical unity. Hank Hanegraaff, director of the Christian Research Institute, considers Lent to be a time when “Christians are to contemplate their sinfulness, repent, ask God’s forgiveness, and realize the infinite sacrifice God made on their behalf.”57 It seems that we have conveniently forgotten the words of the Lord: “Learn not the way of the heathen, and be not dismayed at the signs of heaven; for the heathen are dismayed at them. For the customs of the people are vain …” (Jeremiah 10:2-3); it is impossible to take a pagan festival and convert it into a Christian celebration without showing total disregard for God’s Word. “And hereby we do know that we know him, if we keep his commandments” (1 John 2:3).

Although it might not be surprising for Hanegraaff to embrace Lent, since he has converted to Eastern Orthodoxy, yet even within the broader Evangelical community he finds support. It is becoming increasingly popular among those who call themselves Evangelicals to incorporate some recognition of the pagan/Catholic Lent traditions. “Celebrating Easter wouldn't be the same without observing Lent first … ‘Everything we do during Holy Week [Maundy (washing of the feet) Thursday and Good Friday services] has taken on a much deeper dimension because we’ve just gone through Lent. Then when Easter comes, it seems even more significant since we’ve prepared for it. We’ve spent lots of time thinking about what our faith really means’” (square brackets included in the original; explanation of Maundy added).58 Maundy Thursday is also known as Holy Thursday and is the day before the traditional Good Friday. This quote comes from the leader of a United Methodist church, a group that has historically never included Lent in their practices. Ted Olsen, writing for Christianity Today, made this observation: “For many evangelicals who see the early church as a model for how the church should be today, a revival of Lent may be the next logical step.”59 The early church referred to is the developing Roman Catholic Church, and the step into Lent might indeed be logical (if you’re looking at the Catholic Church), but it is definitely not Biblical.

Since Vatican II, the Catholic Church has reemphasized the baptismal link to the meaning of the season of Lent. It is used as a time of preparation for baptism, or a renewal of the commitments of baptism. They see Lent practices as coming from “three merging sources:”60 “The first was the ancient paschal fast that began as a two-day observance before Easter but was gradually lengthened to 40 days [here is a not-so-subtle hearkening back to ancient Egyptian and Babylonian traditions]. The second was the catechumenate [“the period of instruction in the faith”61 as a process of preparation for Baptism, including an intense period of preparation for the Sacraments of Initiation to be celebrated at Easter. The third was the Order of Penitents, which was modeled on the catechumenate and sought a second conversion for those who had fallen back into serious sin after Baptism. As the catechumens (candidates for Baptism) entered their final period of preparation for Baptism, the penitents and the rest of the community accompanied them on their journey and prepared to renew their baptismal vows at Easter.”62 You’ll notice that none of those “merging sources” is openly acknowledged as having an ancient heritage; they have found “spiritual” sources for their tradition in order to dupe their members into following their lead. A very brief examination of the liturgy of the Stations of the Cross (commonly practiced during Lent, particularly as the time draws closer to Easter) reveals the paganism that has been included by the Catholic Church. Before each station, the opening accepted words are: “We adore You, O Christ, and we praise You. Because, by Your holy cross, You have redeemed the world”; then, at the end of the full recitation, it is also customary to repeat: “Our Father, Hail Mary, Glory be.”63

The cross was not holy (this reveals the Catholic obsession with relics of worship); it was a common Roman cross used to crucify those who had been condemned to death. As we reflect on the sacrifice that Jesus made, where does “hail Mary” come into the picture? It can only come through the Catholic adoption of pagan traditions and applying a veneer of Christianity – making Mary into someone whom she never claimed to be, and in contravention of Scripture. In 1954, Pope Pius XII officially declared Mary to be the Queen of Heaven.64 We read of a “queen of heaven” in Scripture, but it has no reference at all to Mary, the mother of Jesus, nor to anything that is pleasing to the Lord. Jeremiah spoke against those of Judah who had escaped to Egypt, yet who persisted in their commitment to the queen of heaven, and we read of the Lord’s promise to decimate them once again (Jeremiah 44:24-28). Several of the more recent popes have been very vocal concerning their wholehearted commitment to Mary, the Queen of Heaven: “in 1942, Pope Pius XII consecrated the whole Church and the whole world to the Immaculate Heart of Mary”;65 Pope John Paul II claimed the words of a dead Catholic as his very own: “I belong entirely to you, and all that I have is yours. I take you for my all. O Mary, give me your heart”;66 most recently, “before a congregation of more than 100,000 in St Peter’s Square, Pope Francis formally entrusted the world to Mary” (October 13, 2013).67 There can be no denying that the leadership of the Roman Catholic Church is wholly committed to the exaltation of the queen of heaven; what is most dismaying is to see Evangelicals being hooked by the experience of liturgy, and being drawn into Catholic heresy.

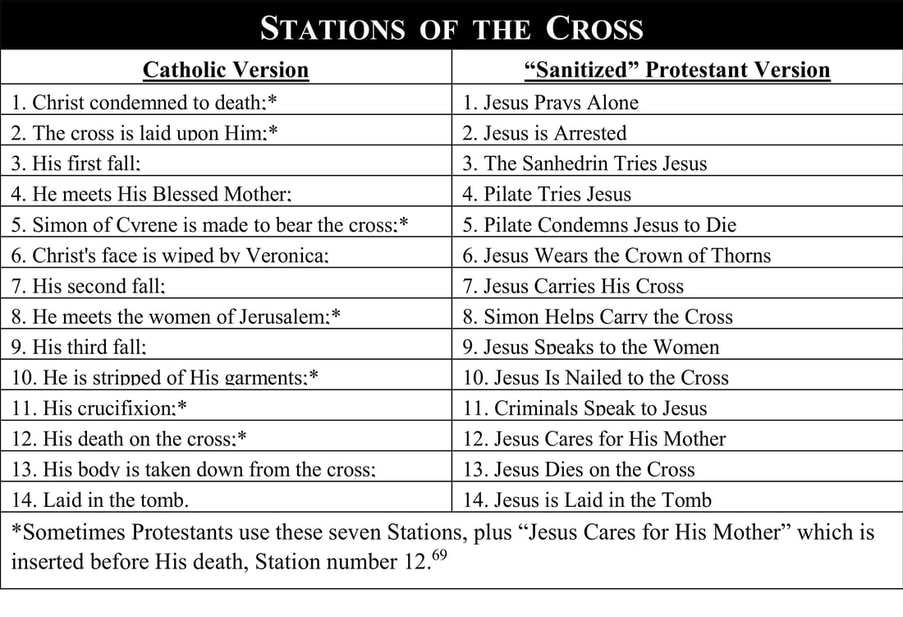

As already noted, during the latter part of the Lent season, it is common for Roman Catholics to practice the Stations of the Cross, something that began with pilgrims to Jerusalem following the Way of the Cross – the route that it was thought that Jesus took from Pilate’s hall to the tomb (the Via Dolorosa, or way of sorrow).68 The focus of these stations (stopping places along the way) is on the sufferings of Christ, specifically His last twelve hours leading up to His burial. During the Middle Ages, going through the Stations of the Cross was considered to be an indulgence – a means of gaining a partial remission of one’s sins – a means of obtaining some “saving grace.” In our day of Ecumenism, even though this practice is generally ascribed to the Roman Catholic faith, it is no longer exclusively a Catholic event. Particularly since the movie, The Passion of the Christ (which closely follows the Stations of the Cross, and was heavily supported by Evangelicals), hit the theatres, there has been a surge of Evangelical openness to many Catholic traditions, and the Stations of the Cross is one of them. A Mennonite friend of ours spoke of attending the Stations of the Cross, and finding them to be of great spiritual blessing; the barriers between the apostasy of the Roman Catholic Church and professing Christians are rapidly disappearing (no, the Catholics are not becoming Christians, but Christians are becoming apostate, or increasingly pagan, as the case may be). There are traditionally fourteen Stations:

Only eternity will reveal how many people have turned away from the truth because of the influence of pagan traditions. The warning that the Lord gave to Israel is very clear: “After the doings of the land of Egypt, wherein ye dwelt, shall ye not do: and after the doings of the land of Canaan, whither I bring you, shall ye not do: neither shall ye walk in their ordinances. Ye shall do my judgments, and keep mine ordinances, to walk therein: I am the LORD your God” (Leviticus 18:3-4). Israel was to walk in the ways of the Lord, not after the traditions of the Egyptians, nor after the manner of the people whom they would supplant in the land of Canaan. Through Jeremiah, the Lord declared: “Learn not the way of the heathen …” (Jeremiah 10:2); yet what is largely accepted as commonplace among Evangelicals today, often finds its roots within the pagan traditions of fallen cultures. Although we might rightly ascribe the responsibility to the Roman Catholic Church for making many of these customs part of our culture, we cannot blame them for our decision to accept them as appropriate for the child of God. Growing up with error only serves to make it more difficult to identify, but it does not make it right. We might feel that the customs of our youth are acceptable without so much as a second thought – but will they stand the test of Scripture?

When my wife and I stepped away from Evangelicalism, it soon became evident that there were many things that we had accepted as being right that needed to be re-evaluated in light of our new commitment to the truth of Scripture. This study is another that I undertook to ensure that our practice was in keeping with the teachings of God’s Word; since that was now our greatest concern, our accepted traditions were brought under the revealing light of the holy, unchangeable Scriptures. Perhaps one of the greatest failures of Evangelical teaching is that there is no encouragement to personally study the Scriptures even though that is what God requires of us; in fact, even the preachers and teachers seem content to accept the traditions that they have been taught as having God’s stamp of approval, without ever checking to ensure that they do. I will never forget the response that I received from an elderly, fundamental-Baptist preacher when I asked him to review the exaggerated case that one of his missionaries had made for a Biblical basis for church membership; his response was simply: “I am a Baptist by conviction. I believe our faith and practice is absolutely inline with what the Word of God teaches.”1 In other words, he believed that his Baptist traditions had God’s approval, yet he was unwilling to test those beliefs to ensure that they were, in fact, in keeping with God’s Word (contrary to 2 Corinthians 13:5); his thought was that if you have a problem with his Baptist traditions, then clearly you’re not a Baptist, and that’s okay (although clearly not the best). His attitude provided me with encouragement to continue to measure all things against the Word of God, to teach what I found to my wife, so that we could change how we lived in order to remain obedient to the commands of Scripture. We have changed many things since leaving the Evangelical community, and it has cost us family and friends, but we are committed to continually seek to know the Truth of God more fully – indeed, His promise is that the one who is diligently seeking is also finding (Matthew 7:8).

As we consider the subject of Easter together, may it be with a desire to know what God has to say on the matter. Within most churches, there are deeply entrenched traditions when it comes to how this time is celebrated, but, if you’re like I was, you may have never taken the time to ask any questions as to why these things are done – perhaps this will be your maiden voyage into discovering the truths of Scripture as never before. It was for my wife and me; God bless you as you read on.

Easter - What’s in a Name?

There is perhaps no greater example of how we have submitted to tradition and failed to exercise our minds in spiritual matters than in the consideration of Jesus’ death and resurrection, and the annual event that is commonly known as Easter. Although the word Easter does appear in Acts 12:4 in the King James Version (KJV), it is an incorrect translation of the Greek word pascha, or Passover; interestingly, the other 28 times that pascha appears in the Greek text, it has always been correctly translated as Passover, nor has it been translated as Easter in most modern translations.2 The translators of the KJV were instructed by King James to follow the pattern of the Bishop’s Bible in carrying out their work, and for some reason, they felt justified to follow that Bible rather than the Greek text;3 the Bishop’s Bible was hastily produced by a number of Anglican bishops in an effort to provide an acceptable alternative to the Geneva Bible, which had become very popular in England and was perceived to be largely Calvinistic because of its many notes.4 Even though the translators of the Bishop’s Bible (1568, and significantly revised in 1572) translated the Greek word pascha elsewhere as Passover, in Acts 12:4 and John 11:55, they chose to use the word Easter, and the KJV translators perpetuated the former error.5 Wycliffe’s translation of 1395 correctly translates the Greek as Passover, however, the subsequent translations done by William Tyndale (1525) and Miles Coverdale (1535) both used the term Easter. Why Tyndale would have done so is somewhat mystifying, as it is said that he translated directly from the original languages.6 Coverdale, on the other hand, depended largely on Tyndale’s work, as he did not have the same grasp of the languages.

The etymology of the word Easter shows its origin in the “O.E. [Old English] Eastre (Northumbrian Eostre), from P.Gmc. [Proto Germanic] Austron, a goddess of fertility and sunrise whose feast was celebrated at the spring equinox.”7 The Roman Catholics, however, do not accept this history for the word, and declare: “The English term [Easter], according to the Ven. Bede [the Venerable Bede, one of their Doctors of the Church, c. AD 672-7358] … relates to Estre, a Teutonic [northern European] goddess of the rising light of day and spring, which deity … is otherwise unknown … The Greek term for Easter, pascha … is the Aramaic form of the Hebrew pesach (transitus, passover)” (bold emphasis added).9 Despite the fact that one of their own (Bede), whom they consider to be a significant contributor to the formulating of their doctrine, exposes the pagan connection, Roman Catholic theologians have chosen to dismiss this association and prescribe Easter as being a correct translation for the Greek word, pascha. However, even though they distance themselves from the pagan relationship and seek to uphold a false translation of the Greek word pascha, their own English Bible translations do not use the term Easter for pascha in either John 11:55 or Acts 12:4.10 Even the oldest Catholic translation of the Bible into English (the Douay-Rheims translation; NT published in 1582) translates the word as pasch, not Easter.11 There appears to be some inconsistency among Catholic scholars as to the correct translation of the Greek pascha, or perhaps they are seeking to justify their general use of Easter.

However, the Roman Catholics are not the only ones who choose to turn a blind eye to the relationship between the word Easter and the pagan goddess of fertility. The late Gretchen Passantino, co-founder of Answers in Action and a contributor to the Christian Research Journal, stated: “Easter is an English corruption from the proto-Germanic root word meaning ‘to rise’.”12 She went on to explain: “It refers not only to Christ rising from the dead, but also to his ascension to heaven and to our future rising with him at his Second Coming for final judgment. It is not true that it derives from the pagan Germanic goddess Oestar or from the Babylonian goddess Ishtar ….”13 This is an attempt by a fairly well-known Evangelical apologist to rationalize the “English corruption” Easter sufficiently so as to make it completely acceptable by denying the pagan connection. Regardless of the spiritual significance that she attempted to assign to the word Easter, the position that she put forward, supposedly debunking the pagan association, was based entirely upon her own authority. She flatly denied that Easter derives from the names given to pagan goddesses going back to Babylon, yet she did not provide any support for her assured declaration. On the other hand, the evidence against her in this matter seems to be quite significant. We have already seen the analysis made by one etymology dictionary that is in opposition to her position. Shipley, in his Dictionary of Word Origins, says that the word is “from the AS [Ango-Saxon] Eostre, a pagan goddess,” and then goes on to state: “The Christian festival of the resurrection of Christ has in most European languages taken the name of the Jewish Passover … in Eng. [English] the pagan word has remained ….”14 He not only identifies Easter as being of pagan origin, but goes on to expose the English language as being quite unique in retaining the pagan term. Another states: “It is significant that in England and Germany the Church accepted the name of the pagan goddess ‘Easter’ (Anglo-Saxon Eostra – her name has several spellings) for this new Christian holiday.”15 Passantino’s opinion on the matter stands alone against some very significant authorities; as nice as it might have been for her to think that the word Easter sprang directly from reference to the resurrection of the Lord, it was clearly only a delusion on her part.

It is commonly held among professing pagans that Eastre is the Anglo-Saxon goddess of fertility, and Ostara is the Germanic goddess and the name of the spring festival that celebrates a time of renewal and rebirth.”16 It seems that all of the ancient civilizations had their version of this goddess of fertility: the Ango-Saxons had their Eastre, Egypt had Isis, Phoenicia - Astarte, Greece - Aphrodite, Rome - Venus, Babylon - Ishtar, and the inhabitants of Canaan had Ashtoreth (1 Kings 11:33). Like many other traditions that are a part of our culture today, the roots of Easter can be traced way back to the Babylonian civilization that was formed out of rebellion against the Lord.

From the descendants of Noah, we find a great-grandson, Nimrod, whose name means “we will revolt.”17 He became “a mighty one in the earth” (Genesis 10:8), which speaks of his greatness as a leader among the people, and a “mighty hunter before [against] the Lord” (Genesis 10:9) that exposes his rebellion against the God of creation.18 If we understand that it is not possible to be in rebellion without first knowing something about what or whom you are rebelling against, then the truth of Romans 1:21 becomes much more striking – “…when they knew God, they glorified him not as God, neither were thankful; but became vain in their imaginations, and their foolish heart was darkened.” Nimrod led a rebellion against God, which simply means that he knew enough about what God required to be fully aware that his actions were in opposition to Him. That rebellion found its ultimate expression in the city and tower that he set out to build in defiance of Jehovah (Genesis 11:4), a city called Babel (Genesis 10:10, 11:9).

Almost all pagan cultures celebrate the vernal equinox in honor of a goddess of fertility: Asase Ya (Ashanti people of west Africa), Isis (Egypt), Bhavani (India), Asherah (Mesopotamia), Éostre (or Ostara, German), Aphrodite (Greek), and Venus (Roman), to name just a few.19 As we have seen, the Catholics, and even some Evangelicals, will attempt to refute the pagan history of Easter (while most will simply ignore it). It cannot be denied that modern-day pagans readily accept this connection: “Easter has deep roots in the mythic past. Long before it was imported into the Christian tradition, the Spring festival honored the goddess Eostre or Eastre.”20

As we consider the use of the term Easter within the context of our cultural celebrations, if we’re honest, we will acknowledge that not everyone has Jesus’ death, burial and resurrection in mind. Nevertheless, it is also evident that, as it is applied to the events surrounding the culmination of Jesus’ earthly ministry, the term is used by virtually everyone today – Christian and pagan alike; however, that does not make it right. We would do well to take to heart the words of Jehovah through Jeremiah that we have already noted: “Learn not the way of the heathen, and be not dismayed at the signs of heaven; for the heathen are dismayed at them” (Jeremiah 10:2). This was a warning to Israel that they were to be a separate people, and, likewise, it is a warning to us to guard against being taken in by the ways of the world.

We have already noted the warning that the Lord gave to Israel before they ever entered the Promised Land (Leviticus 18:3-4) – a warning to be separated from the traditions of the pagan cultures of Egypt and Canaan. The Lord’s specific instructions to Israel was that they were not to adopt the pagan customs of the people where they were going (Canaan), nor were they to take with them the practices of the people whom they had left behind (Egypt). God desired a holy people: “… if ye will obey my voice indeed, and keep my covenant, then ye shall be a peculiar treasure unto me above all people: for all the earth is mine: and ye shall be unto me a kingdom of priests, and an holy nation” (Exodus 19:5-6); yet as we consider Israel’s history, we realize that God’s desire for them never happened. Interestingly, we find that Peter made a similar comment regarding those who are in Christ: “…ye are a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, an holy nation [people], a peculiar people [an acquired people]; that ye should shew forth the praises of him who hath called you out of darkness into his marvellous light” (1 Peter 2:9).21 Yet, what do we find today among those who claim to be God’s people? When they speak of Jesus’ death, burial and resurrection, they refer to it by the name of a pagan goddess of fertility whom pagans celebrated at the time of the spring equinox. Surely Satan must laugh at the gullibility of today’s professing Christians; he has managed, while working through a corrupt branch of church history, to get Christians everywhere to refer to the greatest demonstration of God’s love for mankind by the name of a pagan goddess. How could we? How dare we so profane God’s righteous act of sacrifice to secure our redemption! Although we may be gratified that we are not following “after the doings of the land of Canaan” (we are not following the pagan rituals of our society), yet we may well be guilty of perpetuating “the doings of the land of Egypt” (continuing the error from past days).

Constantine I

How did we fall into this trap of perversion? Once again, we need look no further than the budding Roman Catholic Church of the fourth century. In an effort to settle what had become a rather lively dispute as to when the death, burial and resurrection of the Lord should be remembered, the determination of when Easter was to be celebrated was made by the Council of Nicea in the year AD 325. “These Paschal controversies … ended with the victory of the Roman and Alexandrian practice of keeping Easter … on a Sunday, as the day of the resurrection of our Lord.”22 Although the specifics of this did not come out in any of the canons of the Council, their determination was this: “The feast of the resurrection was thenceforth required to be celebrated everywhere on a Sunday, and never on the day of the Jewish passover, but always after the fourteenth of Nisan, on the Sunday after the first vernal full moon.”23 The circular from the Council of Nicaea that was sent out by Emperor Constantine declared: “we would have nothing in common with that most hostile people, the Jews”; in other words, “the leading motive for this … [calculation of when to celebrate Easter] was opposition to Judaism.”24 Although the consensus was that it was to never fall on the day of the Jewish Passover, they had no problem aligning it with the common godless (and goddess) celebrations. At the time of Constantine, there was a growing undercurrent of anti-Semitism that was often reflected in the decisions that were made – they could practice anything except that which gave the appearance of being remotely Jewish. What is beyond comprehension, is that they shunned anything Jewish (even though Jesus was a Jew) yet had no difficulty embracing what was totally pagan – one more time, Satan could laugh at the spiritual efforts of self-righteous men. This became the pattern that the leaders of the emerging Roman Catholic Church followed in a twisted effort to make “Christian” celebrations the practice of the majority of the common people – something that would garner the favor of the emperor, which they sought with a growing frenzy. By using the pagan festivities that already existed, the bishops simply changed some of the names involved; the pagans didn’t care as they were used to the names being changed, and the “Christians” could then celebrate at the same time – everyone in the empire would be together during the days of the festival. A thin veneer of “Christian” whitewash was all that was needed to unite the empire, gain the favor of the emperor, and everyone was happy, but no one considered that God would not be impressed. Today, sincere Evangelicals and Fundamentalists speak the name of the ancient goddess of fertility without a second thought, and they faithfully train the next generation to perpetuate the error – something that must be particularly loathsome to our holy God.

When Joshua reached the end of his life, he spoke words of encouragement and challenge to the leaders of Israel: “Be ye therefore very courageous to keep and to do all that is written in the book of the law of Moses … that ye come not among these nations, these that remain among you; neither make mention of [or, invoke] the name of their gods … But cleave unto the LORD your God …” (Joshua 23:6-8).25 In this, he echoed Jehovah’s words through Moses: “…in all things that I have said unto you be circumspect [take heed, guard]: and make no mention of [do not invoke] the name of other gods, neither let it be heard out of thy mouth” (Exodus 23:13).26 The Psalmist, likewise, understood the Lord’s requirement in this regard: “Their sorrows shall be multiplied that hasten after another god: their drink offerings of blood will I not offer, nor take up their names into my lips” (Psalm 16:4). Is it a small thing that the name of the goddess of fertility slips unnoticed from the tongues of Christians today as they refer to the sacrifice of the Lord Jesus Christ for the sins of the world? Paul asked this question: “What fellowship hath righteousness with unrighteousness?” (2 Corinthians 6:14) – the required answer is still, “None!”

The text of Scripture declares: “For I have received of the Lord that which also I delivered unto you, That the Lord Jesus the same night in which he was betrayed took bread: And when he had given thanks, he brake it, and said, Take, eat: this is my body, which is broken for you: this do in remembrance of me. After the same manner also he took the cup, when he had supped, saying, This cup is the new testament in my blood: this do ye, as oft as ye drink it, in remembrance of me. For as often as ye eat this bread, and drink this cup, ye do shew the Lord’s death till he come” (1 Corinthians 11:23-26). This is the Biblically-prescribed method for remembering the Lord.

Today there are elaborate dramatic presentations of the “passion play” all around the world (depicting the events surrounding Christ’s crucifixion), and many churches are sure to include a dramatic production of some aspect of the Lord’s suffering during the spring season. Perhaps the most well-known, large-scale production is Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, which not only went to great lengths to dramatize the gore of the crucifixion, but also very carefully followed the Roman Catholic tradition of the Stations of the Cross. The dramatic plays have become a tool used by Satan to draw everyone together in Ecumenical unity and cooperation; our local ministerial association has not been exempt from such doings – but why would they be? This is the whole point of coming together. The passion play concept became a part of the early church rituals during their “Good Friday” celebrations (again, this is something with a long-standing history). Then, in the 19th century, there began a rejuvenation of the historic plays, and they have continued to grow in popularity.27 However, this is not how the Lord arranged for us to commemorate His death; He has laid out very clearly how we are to remember Him, and it includes no dramatic recreations of what we think might have taken place at Calvary, or anywhere else; beyond that, one thing is absolutely certain – there is undeniably no call to commemorate Christ’s suffering under the name of a heathen goddess.

Good Friday & Easter Sunday vs. Truth

As we consider Good Friday (commonly thought, by Evangelicals, Fundamentalists and Liberals alike, to be the day of Christ’s crucifixion), it is important that we base our understanding of the timing of the events surrounding Jesus’ death, burial and resurrection on reality, and not on what has been passed down to us. Today’s calendar shows a day called Good Friday followed by a regular Saturday, and then Easter Sunday. Typically, the understanding is that Jesus died on Friday, and was raised to life on Sunday; this fits nicely with our inherited calendar and the way that Easter is celebrated today (using the term with the full understanding of its pagan origins). To quote from Hank Hanegraaff, director of the Christian Research Institute and host of the Bible Answer Man radio program, “In Matthew 12:40 Jesus prophesies that He would be dead ‘three days and three nights.’ The fact of the matter is he was dead for only two nights and one full day.”28 He justifies this blatant contradiction of Jesus’ own words by saying that the Jews counted any portion of a day as a whole day. However, Jesus’ words to the Pharisees that Hanegraaff so casually dismisses, seem very clear: “For as Jonas was three days and three nights in the whale’s belly; so shall the Son of man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth” (Matthew 12:40). Why would Jesus, the eternal Word Who framed the first evening and morning (Genesis 1:5), say “three days and three nights” if He meant only one day and two nights? Specifically stating “three days and three nights” would rule out Jesus counting a portion of a day as the whole day; He is very specific about the number of days and nights that would be involved. Counting from Friday to Sunday will never permit the fulfillment of these words of Jesus, yet this is rationalized away, and the average Evangelical today, including the so-called “Bible Answer Man,” carries on without giving the matter another thought. Even more surprising, it seems that even the very vocal Fundamentalists, who are often critical of Evangelicals, have joined the mindless by “going along” with the crowd rather than seeking the truth, and then doing their part to make that truth known. It is way too late to stem the slide, but it’s never too late to stand for the truth.

In light of the terrible desecration of calling our Lord’s death, burial and resurrection by the name of a pagan goddess, it is incumbent on us to give careful consideration to the timing of the events of Jesus’ sacrifice and resurrection so that we do not add thoughtless error to blasphemy. We have already seen Hanegraaff’s careless acceptance of the Catholic tradition (for that’s exactly what the “Good Friday-Easter Sunday” combination is), and we must be cautious that we do not fall into the same simplistic, non-thinking pattern. To begin our consideration, it is important that we hold in our minds that the Jewish method of keeping time is not the same as what we practice in our culture today. The Jewish day begins at about six o’clock in the evening, and is in keeping with the Genesis account of creation where God declared the “evening and the morning” to be the day (Genesis 1:5, 8, 13, 19, 23, 31). We need to keep this firmly in mind when viewing the events surrounding Jesus’ death and resurrection, lest we arrive at conclusions that are based on an incorrect premise.

Leviticus 23:5 tells us that “in the fourteenth day of the first month at even is the Lord’s passover.” The first month in the Jewish calendar is called Abib or Nisan (the latter was primarily used after the Babylonian captivity, and seems to be rooted in the Assyrian word nisannu, meaning “beginning”29). This is in the spring of the year, and is the month in which the Lord brought Israel out of Egypt. For ease of looking at the details of the days surrounding the Passover as they unfolded at the time of Jesus’ death and resurrection, it is of value to plot them into a chart format so that they can be observed clearly and chronologically.30 See Chart.

Incredibly, by taking the time to read the Scriptures carefully, it is not difficult to determine that Jesus fulfilled His statement to the Scribes and Pharisees that He would be in the earth three days and three nights (Matthew 12:40). It is not necessary to rationalize Jesus’ words away, or to manipulate the text in order to see that His words were fulfilled with great precision. For the purposes of our study, it is important to recognize two truths that have failed to hit the radar of Evangelicals and Fundamentalists alike: 1) the Lord Jesus Christ did not die on “Good Friday,” but rather on Wednesday, the 14th of Nisan, as our Passover Sacrifice (1 Corinthians 5:7), and 2) He did not rise on “Easter Sunday,” but rather at the end of the Sabbath, our Saturday evening. What we have seen in the Scriptures is a clear discrediting of the modern concept of “Good Friday” and “Easter Sunday” – products of the zealous Roman Catholic leadership to “Christianize” the pagan celebrations already in common practice. Once again, we must remind ourselves: “Learn not the way of the heathen …” (Jeremiah 10:2), and “… what communion hath light with darkness?” (2 Corinthians 6:14); the former being a “thus saith the Lord” to which we would do well to give heed, and the latter being a rhetorical question to which the answer is: “None!!”

Carnival or Mardi Gras

We might not typically relate what has become a time of wild partying as having any relationship at all with Jesus’ death and resurrection, and we would be Biblically correct. As I grew up, a carnival was always considered to be a travelling amusement show that would include rides, clowns, and cotton candy. However, historically, Carnival has referred to the general time before Lent, which is a season of fasting and self-denial leading up to Easter; today it is primarily the three days prior to Ash Wednesday (which signals the beginning of Lent), although there are still some regions that begin the celebrations as early as November. However, indications are that the celebration of life (Carnival) originally began December 26, and built to a climax just before Lent;41 the common element to all forms of this celebration is that it ends on the day before Ash Wednesday. The term Carnival comes from an old Italian word that literally means “raising flesh,” but folk etymology has it coming from Latin meaning “flesh, farewell.”42 Mardi Gras, as it has come to be known in many regions, is from the French for “fat Tuesday,”43 and gives some indication of the excesses that take place prior to the fasting period of Lent that begins the next day on Ash Wednesday.

The Carnival celebrations date back to the ancient Greek spring festivities in honor of Dionysius, the god of wine.44 The Romans adopted the celebration and merged it with their Bacchanalia (a spring festival in honor of Bacchus, their god of wine and revelry) and Saturnalia (their celebrations around the winter solstice). The Roman Catholic leaders then adapted the pagan festival to lead up to their season of Lent, with the primary celebrations taking place just before Lent. In essence, it became a time of excess before a time of restraint. “Carnival … was a giant celebration in which rich food and drink were consumed, as well a time to indulge sexual desires all of which were supposed to be suppressed during the following period of fasting” (bold in original).45 Mardi Gras is not something that we typically associate with the Roman Catholic Church, perhaps a reflection of the Church’s desire to distance itself from the debauchery of this celebration. Nevertheless, the association with paganism is very evident, and the culmination of this festival lands on the doorstep of Lent, which we all relate to the Roman Catholic Church.

Ash Wednesday and Lent

Ash Wednesday is the first day of the season of Lent, a forty-day period of abstinence and reflection leading up to Easter (I freely use the term inasmuch as these all bear pagan roots). Ash Wednesday derives from the ancient practice of applying ashes to the head, or forehead, of an individual as a sign of humility before God. “Ash Wednesday is a somber day of reflection on what needs to change in our lives – if we are to be fully Christian.”46 Within the Catholic tradition, it is a time to ponder those things that we need to do differently in order to be “fully Christian”; it is another aspect of the works-oriented salvation that characterizes Roman Catholicism.

What is interesting to notice is that this practice, which has traditionally been connected with the Roman Catholic Church, has been quickly moving into Evangelicalism. Belmont University in Nashville, Tennessee, an Evangelical university with Baptist roots, in 2009 held an Ash Wednesday service led by a local Catholic bishop.47 In 2010, the service was co-officiated by Belmont’s own Vice-President of Spiritual Development; the Catholic Bishop of Nashville gave the message “followed by the marking of the ashes.”48 There is a movement among Evangelicals toward the liturgical – we see this very specifically evident within the Emergent church, where there is a very pronounced shift back to ancient practices (where they originate is not a matter of concern to them), and the Catholic Church is a primary source for most of these traditions.

The history of Lent seems to be cloaked in a shroud of mystery; claims are made that it was kept from the days of the Apostles but that is speculative – it is mentioned in the canons of the Council of Nicaea (AD 325).49 Canon V suggests a meeting of the bishops twice each year: “the one before Lent … and let the second be held about autumn”; lent is from the Latin Quadragesimae, which simply means the fortieth.50 Evidence for Lent being a fast of 40 days does not seem to appear until after the Council of Nicaea.51 Within the culture of ancient Egypt, Osiris (god of the dead and living [resurrected])52 was “supposed to be dead or absent forty days in each year” and during this time the people would mourn his loss;53 such rites were common among the ancient nations during the times when the land was unproductive, and this period of mourning was followed by a joyous celebration at the vernal equinox – the beginning of springtime.54 Although such pagan connections are generally not acknowledged by those who keep Lent (which now includes some Evangelicals), the reality is that there is no Biblical record establishing this tradition, but we find many warnings against adopting pagan practices. The Roman Catholic Church will, from time-to-time, admit that there is a pagan connection to many of its special days: “The reasons for celebrating our major feasts when we do are many and varied. In general, however, it is true that many of them have at least an indirect connection with the pre-Christian [pagan] feasts celebrated about the same time of year — feasts centering around the harvest, the rebirth of the sun at the winter solstice (now Dec. 21, but Dec. 25 in the old Julian calendar), the renewal of nature in spring, and so on.”55 The calendar of the Catholic Church is filled with festivities and commemorations that have grown out of their practice of “sanitizing” pagan celebrations. “They [the Egyptians] claimed the merit of being the first who had consecrated each month and day to a particular deity; —a method of forming the calendar which has been imitated, and preserved to the present day; the Egyptian gods having yielded their places to those of another Pantheon [Roman paganism], which have in turn been supplanted by the saints of a Christian [Catholic] era ….”56 Very little has changed; paganism willingly changes its appearance to find acceptance in every era – Satan loves religion and so changing names for different pagan deities is not a problem.

Within the Catholic tradition, the forty days of Lent are seen as a time of prayer, fasting and almsgiving in preparation for the celebration of the Easter season. This would be a time for the nominal Catholics to renew their fervency by going to confession and doing the prescribed penance – sacramental acts that bear soul-saving properties (according to their tradition).

However, as already noted, Lent is no longer just for pagans and Roman Catholics; Evangelicals are not about to be left behind in anything that will promote Ecumenical unity. Hank Hanegraaff, director of the Christian Research Institute, considers Lent to be a time when “Christians are to contemplate their sinfulness, repent, ask God’s forgiveness, and realize the infinite sacrifice God made on their behalf.”57 It seems that we have conveniently forgotten the words of the Lord: “Learn not the way of the heathen, and be not dismayed at the signs of heaven; for the heathen are dismayed at them. For the customs of the people are vain …” (Jeremiah 10:2-3); it is impossible to take a pagan festival and convert it into a Christian celebration without showing total disregard for God’s Word. “And hereby we do know that we know him, if we keep his commandments” (1 John 2:3).

Although it might not be surprising for Hanegraaff to embrace Lent, since he has converted to Eastern Orthodoxy, yet even within the broader Evangelical community he finds support. It is becoming increasingly popular among those who call themselves Evangelicals to incorporate some recognition of the pagan/Catholic Lent traditions. “Celebrating Easter wouldn't be the same without observing Lent first … ‘Everything we do during Holy Week [Maundy (washing of the feet) Thursday and Good Friday services] has taken on a much deeper dimension because we’ve just gone through Lent. Then when Easter comes, it seems even more significant since we’ve prepared for it. We’ve spent lots of time thinking about what our faith really means’” (square brackets included in the original; explanation of Maundy added).58 Maundy Thursday is also known as Holy Thursday and is the day before the traditional Good Friday. This quote comes from the leader of a United Methodist church, a group that has historically never included Lent in their practices. Ted Olsen, writing for Christianity Today, made this observation: “For many evangelicals who see the early church as a model for how the church should be today, a revival of Lent may be the next logical step.”59 The early church referred to is the developing Roman Catholic Church, and the step into Lent might indeed be logical (if you’re looking at the Catholic Church), but it is definitely not Biblical.

Since Vatican II, the Catholic Church has reemphasized the baptismal link to the meaning of the season of Lent. It is used as a time of preparation for baptism, or a renewal of the commitments of baptism. They see Lent practices as coming from “three merging sources:”60 “The first was the ancient paschal fast that began as a two-day observance before Easter but was gradually lengthened to 40 days [here is a not-so-subtle hearkening back to ancient Egyptian and Babylonian traditions]. The second was the catechumenate [“the period of instruction in the faith”61 as a process of preparation for Baptism, including an intense period of preparation for the Sacraments of Initiation to be celebrated at Easter. The third was the Order of Penitents, which was modeled on the catechumenate and sought a second conversion for those who had fallen back into serious sin after Baptism. As the catechumens (candidates for Baptism) entered their final period of preparation for Baptism, the penitents and the rest of the community accompanied them on their journey and prepared to renew their baptismal vows at Easter.”62 You’ll notice that none of those “merging sources” is openly acknowledged as having an ancient heritage; they have found “spiritual” sources for their tradition in order to dupe their members into following their lead. A very brief examination of the liturgy of the Stations of the Cross (commonly practiced during Lent, particularly as the time draws closer to Easter) reveals the paganism that has been included by the Catholic Church. Before each station, the opening accepted words are: “We adore You, O Christ, and we praise You. Because, by Your holy cross, You have redeemed the world”; then, at the end of the full recitation, it is also customary to repeat: “Our Father, Hail Mary, Glory be.”63